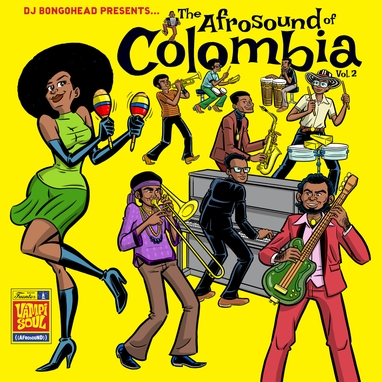

Vampisoul is back with a fresh batch of funky, folky and psychedelic tropical bangers from the deep vaults of Discos Fuentes (and its other properties, Tropical and Machuca). As previously stated in the first volume of this series, the term ‘Afrosound’ is an invented concept appropriated from Discos Fuentes. If the term seems a bit vague or slippery, rest assured that with this second installment you will come closer to understanding the Afrosound aesthetic. You’ll also grow to appreciate the diversity and unpredictability of talent under the Fuentes umbrella.

Afrosound is used to denote a thrilling and sometimes freaky soundtrack that chronicles the acceptance, evolution, diffusion and mainstreaming of the country’s rich Afro-coastal heritage over a 30-year period. The music was taken from the Caribbean and largely agrarian savannah departments and transported inland to the country’s more industrialized mountain regions, where it was translated, simplified, mass marketed, manufactured, recycled, modernized and globalized (with additives from distant shores). It was then packaged with a sexy lady on the cover and thanks to Don Antonio Fuentes’ music mogul vision, sold to Latin America (and later the world at large) in order to make it dance to his beloved costeño rhythms. Through Fuentes and other labels like Codiscos and Sonolux, the raw resources of this Afrosound culture were melted down and shaped into black wax and diffused outward in all directions from the antioqueño cities of Medellín and Bogotá, where the major bulk of the music production industry resided in the 50s through the 80s. This Afro-vibration was sent out from the cold, misty high mountains and bounced back down to the flattened plains, meandering rivers, verdant valleys, steaming jungle and whispering shores of the azure sea, where it was resold to the original regions that inspired it and traveled to further lands beyond the horizon, like Mexico, Peru, Venezuela, Argentina. There were also several smaller coastal-based labels like Curro and Tropical that did much the same thing, but maintained a local base of operations for their work. You would have found this sound in little moldy hardware, musical instrument and dry-goods stores, or broadcast on radios in buses, cars, trucks, fishermen’s canoes, even lashed to burros. It blasted in bars, hotels, on beaches from transistors. It was played on the booming sound systems at the outdoor black champetero parties under the palm trees and in the palenques, social clubs and house parties in working-class barrios, on crackling loudspeakers blaring from street festivals, in plazas. This incredible stream of black gold adorned and enriched the public airways of Cali, Buenaventura, Cartagena, Baranquilla, to become a symbol of pride and part of Colombia’s collective identity.

Afrosound is not really something tangible that can be tied down and bound to a critic’s rules. Nor is it some venerable folkloric strain passed down through generations from time immemorial. It’s a modern bastard hybrid, syncretic and synthetic, spawned in the studio, co-opted by government, commodified by an industry that could only have been born in the era of the global village. It is more accurate to think of it as a state of mind, a way of creating, playing, seeing and hearing. The unifying factor of this second volume is still the same: African roots or influences and the period of experimentation, self expression, upheaval, rebellion and rebirth in the industry, nurtured by Discos Fuentes and its stable of musicians, producers and engineers.

Vampisoul

Additional information

| Weight | 350 g |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 33 × 0.3 × 33 cm |

| Artist | |

| Genre | |

| Label |